They've been here a while in

BLACK HARLEM. You've seen those guys with the napsacks and the tight white shirts with the black nametags walking all over place. You knew it would only be a matter of time before a temple pops up-that church

has a lot of dough! Check out the articles below Let the battle for black souls begin!

A feeling of belongingFor Mormons in Harlem, a bigger space beckons

By Andy Newman The Salt Lake Tribune

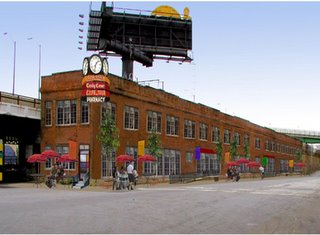

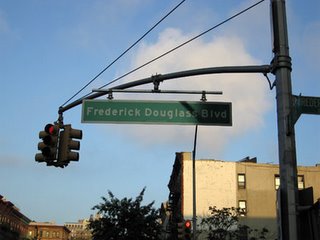

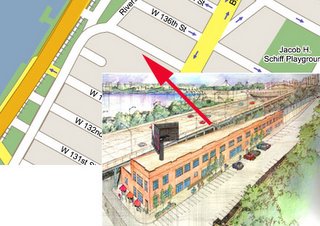

The pilgrims' progress began in a back dining room at Sylvia's. In 1997, a handful of members of the Mormon church began meeting on Sundays in a mirror-lined banquet hall at Sylvia's restaurant, the venerable cathedral of soul food in Harlem. Now, after seven transitional and increasingly cramped years in a windowless brick shoebox on West 129th Street, the congregation is moving around the corner to a gleaming new five-story structure on Malcolm X Boulevard, one of Harlem's main arteries. Never again will the members have to cut services short to make way for Sylvia's overflow brunch crowd. There is only one problem with the new building, in the view of Herbert Steed, whose title with the newly established Harlem First Ward of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints is first counselor. "I think it's going to be too small soon," he said. As they have across the world, the Mormons continue to multiply in the New York City region, from one congregation in 1965 to several dozen in 1985, to 129 today, serving more than 41,000 members. Last year the church opened a temple - a place where high rituals are performed - across from Lincoln Center. It is the only Mormon temple between Washington, D.C., and Boston. But church leaders point with special pride to their expansion in Harlem. They say they hope it dispels any lingering misconceptions that the church, which until 1978 barred blacks from full membership, remains a bastion of whiteness. A 1998 survey by a Mormon and amateur sociologist, James Lucas, found that about 20 percent of Mormons in New York City were black. "We're not in Harlem because of affirmative action," said Ahmad Corbitt, the church's Northeastern public affairs director, who is black. "We're in Harlem because we love people." The new building, a bright red-brick haven scheduled to open by month's end, looks a bit like a schoolhouse topped by a 50-foot steeple. The resemblance is apt: Much of the space is filled with classrooms for religious education and a gymnasium that the church promises to open to the neighborhood. The sanctuary seats 350, and the baptismal font accommodates full-body immersions. The soon-to-be-former place of worship, in contrast, recalls nothing so much as the waiting room of a government office, with dingy industrial carpeting, folding chairs, fluorescent lights and a dropped ceiling. As at most Mormon churches, the walls are bare. The only visual clue to the room's function is the list of hymn numbers posted at the front. But last Sunday, as usual, the 150 chairs were filled and people stood at the back. Also as usual, the room was one of the most racially integrated in Harlem, with about equal numbers of white and black worshipers. (The Mormons have separate congregations for Spanish speakers.) The members approved a formal upgrade of the congregation from a branch, the smallest worship unit, to a ward, which must have at least 300 members. Then, after sharing a sacrament of

white bread and water, they took turns speaking. (The Mormon church does not have specialized clergy, and preaching duties rotate among its members. Most adult males are ordained priests, which entitles them to perform marriages and baptisms. While women cannot be priests, they do preach and teach.) "Because we stood strong together, this is what happened," a founding member of the congregation, Polly Dickey, 59, testified through tears. "This is what this church is about. As long as we stay together, we can accomplish anything." The Mormon church, founded in 1830 by Joseph Smith Jr., is one of the fastest-growing religions in the world, with more than 12 million members; half are in the United States, mostly in Western states. It is based on what Smith said were transcriptions of gold tablets he had found hidden in a mountain in upstate New York, which told the story of a lost tribe of Israel that fled to the New World and was eventually wiped out. Many members of the Harlem church said they had tried several other religions before being converted by Mormon missionaries who came to their doors. "It's the common sense of it," said Wilbertine Thomas, 53, a Baptist-turned-Catholic who was baptized in February. "At Our Lady of Lourdes, they don't tell you the details of how to live your life." The "details" part of the service came when partitions went up and the congregation broke into study groups. A dozen of the newest members, mostly black, gathered in a back room to learn Gospel essentials from three well-scrubbed young white teachers in short-sleeved white shirts and ties. One teacher, Blake Carter, a graduate student at Columbia University,

narrated a lesson in obedience, using the other two as actors. The young man who did as his parents instructed was rewarded with car keys and an extended curfew. The one who rebelled and stayed out late was arrested. Carter deployed his tie as a makeshift set of handcuffs. "We have the obedient one who has freedom," Carter said. "Then we have the disobedient one - what's his situation?" "He really has no freedom now," Thomas said. Exactly, Carter said: "

You gain freedom by obedience to God's commandments and obedience to man's commandments: the local laws. Commandments are just blessings waiting to happen." The newest member, Bruce Rochester, who works restoring tires and who was attending only his fourth service, said that though he had been looking for a religious home after his wife died last year, he never pictured himself as a Mormon. "When the missionaries came, I thought when I saw the church it was going to be a one-sided race thing," said Rochester, 55, who was wearing an electric-blue dress shirt and tie. But he said he quickly learned otherwise. "I've been to churches that have different races, but this is different," Rochester said. "There's more love. I felt like I belong here. I hardly ever felt that at other churches."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE CURSE OF CAIN

Race, religion and reconciliation in the Mormon Church

By Brian WoodwardOn the first day of June in 1978, Spencer W. Kimball and his 14 apostles prayed for an answer to a perplexing spiritual question. In Salt Lake City that summer, questions about the Curse of Cain doctrine of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a church known commonly as the Mormons, had become such an incessant din that church leaders like Kimball knew they would soon have to give an answer. Until then the Curse of Cain doctrine barred blacks from the Mormon priesthood. The doctrine was the Mormon variant of a biblical interpretation most often based on a story in the Book of Genesis. Years before Joseph Smith founded the Mormon Church in upstate New York in the 1820s, Southerners used roughly the same rationale to justify owning slaves. The interpretation is based on the story of Ham, the cursed son of Noah, who was sent to Africa and eventually bore a son named Canaan. Canaan’s family became the tribes that filled Africa through the centuries and so it is assumed by some that the curse placed on Ham is symbolized by black skin. It is one of the most enigmatic and controvertible stories in the Bible, and one that still divides theologians and scholars. It takes an even more peculiar form

in the Mormon cannon, which includes the Holy Bible, and three additional books: The Pearl of Great Price, The Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants. The Curse of Cain doctrine within Mormonism derives from a combination of the Genesis story and two passages in the Pearl of Great Price. The book, written by Joseph Smith, says in its Book of Moses that the original curse was placed upon Cain after Cain murdered Abel so that "… any finding him should kill him." It goes on, in the Book of Abraham, to talk about how Ham later married a daughter of Cain and from that marriage sprang a "a race which preserved the curse in the land." Nowhere in any of Mormonism’s books is the ban from the priesthood stated expressly but based on those two passages, the church made it a matter of practice. It began sometime after the beginnings of the church, though an exact date is unknown to scholars, and there are records of blacks like Elijah Abel having been ordained in the early days of the church. But from the mid-1800s until the late 1970s, the ban held solid. By the summer of 1978, pressure fell on the church from civil rights groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. They staged protests against the church through boycotts of Mormon-owned businesses and many athletes refused to participate in competition against Brigham Young University, the church-sponsored school in Provo, Utah. The pressure also came internally. It stemmed from a concern with universalizing the Mormon message. At the time, a newly constructed temple, the first in church history in an area with a large number of blacks, had gone up in Sao Paulo, Brazil. But because the Curse of Cain prohibited blacks from holding the Mormon priesthood, there were few members who could receive the rights and ordinations of temple worship, a central aspect of the Mormon faith. And so President Kimball, also considered the prophet, seer and revelator of the church, and the 14 high apostles retired to the uppermost chambers of worship in Temple Square at the center of Salt Lake City seeking divine revelation that June. The answer, delivered to the world through Kimball a few days later, changed the Mormon church forever. The opening of the priesthood to blacks was especially monumental for Mormons, because nearly every male member of the church holds a rank in the priesthood. Kimball’s revelation, which lifted the ban, both quelled the NAACP protests and opened the world to Mormon missionaries. It has since helped the church nearly triple in size, to more than 10 million members worldwide. Though the church does not keep statistics on its racial composition, the most rapid growth has occurred in countries with large black populations and has been especially rapid in South America, the Caribbean and Africa, according to church headquarters. In the 20 years since the revelation, Mormonism has struggled with its own form

of integration here in America. Like the pressures Kimball faced, the difficulty is both external and internal. Of the stereotypes still attached to the church from the outside, racial exclusivity is second only to polygamy. The public information office of the church fields so many questions about the two issues that it has included responses on its web site under a section labeled "misconceptions about the church." The struggle continues internally, too. Especially in the lives of members Darius Gray and Ron Anderson. Gray, a black man who has been a member of the

nearly all-white church in nearly all-white Utah since 1963, has a personal knowledge of race and the church that can be told in the first person. Anderson, who is white, is the bishop of the church’s recently formed branch in Harlem, a branch that is nearly all black and Hispanic.

Today, 22 years after their church fully integrated, the lives of Gray and Anderson are still affected daily by the coexistence of race and religion. While that combination may seem incongruous, especially in Mormonism, both say a deeply personal faith and an unwavering belief in the gospel has overpowered everything from pride to critics to their own self-doubt.

A Genesis in the Desert Darius Gray had already been a member of the church for 14 years when Kimball had his revelation in 1978. Gray joined in 1963 when he, like most of black America, was struggling for equal social and legal footing in America. His introduction to the Mormons came through a white family who lived in his mother’s neighborhood in Colorado Springs when he was in his 20s. Like almost all conversions, it was fostered through a series of lessons taught by young Mormon missionaries who visited with him several times that summer and fall. The missionaries explained to him early on that the core of the church’s organizational system was its priesthood. They told him that the priesthood was an integral, almost essential part, for the church, which depends on its lay clergy. They glinted over a part of the teaching dealing with restrictions on the priesthood related to what they called genealogy, telling Gray they would get into it more "later." "Later" came that December, on the night before Gray was to be baptized. In a meeting given to all converts to the church in the final hours before their

baptism, the missionaries asked Gray if he had any final questions of them. The issue of the genealogy of the Lamanites and the Nephites and all the talk of the scattered tribes of Israel and a curse placed on Cain had stuck in Gray’s mind and he had asked himself the question, "How in any way does that relate to me?" As his final question before baptism, he asked it of the missionaries. "That’s when I was told that because of my race I would not be allowed full membership in the priesthood," Gray said. "And I couldn’t believe what I was hearing." He returned home, confused and devastated, and told himself there was no way he was going through with the baptism the next day. "I was not prepared to take a backseat to anyone," he said. It went counter to everything else happening in America and in his own life at the time.

"I was faced with a conundrum," he said. "The problem was that I had already developed a testimony. My pride, my self-respect could not accept the facts of what they were telling me, but I had received a personal revelation. It wasn’t that the church was just or unjust, just that the gospel was true." And so two days later, Gray attended his first Sunday service as a baptized Mormon. As he paced nervously in the hall outside the chapel, where he was waiting to be introduced to the congregation, he saw a young blond girl, who he remembers today only as "not old enough to be in school, with her hair in a ponytail." She played innocently in the hall near him. But when she saw him she stopped and froze. Gray looked down at her and offered a simple, "Hello." Frightened, the girl darted past and toward the end of the hall crying words

that still echo in his memory today. "Mommy, mommy," she said, "a nigger." A few minutes later Darius Gray was introduced to his new congregation for the first time. Through the next 14 years, Gray lived an almost model Mormon existence. He moved to Salt Lake City and became active in the church and the community. He worked as the only black television reporter in his market, and made friends with church elders. He became schooled in church history and scripture. He even led a multiracial support group for those whose lives had been affected by the church’s policy toward blacks. But in one crucial way, Gray was not a model Mormon, and it was a reality he never thought would change. "I am not an apologist for the LDS Church," he said. "But people make mistakes. Whether it is Moses or Joshua or a past president of this church. There has only been one perfect soul to walk this earth." This unrelenting belief carried Gray through 14 years of exclusion and has helped him even in the last 22 years as the church has continued to study and practice the Mormon faith. Gray has also continued his work with the support group, which eventually won official support from the church in the early 1970s

and has grown to include 250 regular members who attend monthly meetings and a mailing list of more than 1,000. Today Gray runs a small business from his home and this August will release the first of a trilogy of books on the history of blacks in the Mormon church, "Standing on the Promises." Gray calls the books "historical fiction" and he has worked with Margaret Blair Young, a professor at BYU, in writing the series. He is a bishop in the church and still president of the Genesis Group, which has yet to be designated an official "branch" or congregation by church elders. "This was not something I expected to happen in my lifetime,’’ Gray said. "But it happened because God was ready for us to make a change. The point is that God wanted us to change. All of us. To become more Christ-like." till the change seems to come slow sometimes, but Gray takes it today in good humor. He said he recently received a call from church elders telling him they needed to pass on a complaint filed to their office by a woman who had attended one of the Genesis group services. " ‘She said you are going Baptist on us,’ they told me," Gray said with a laugh. "Maybe, I guess you’re not going to find people standing up clapping in a normal LDS service." At Home in Harlem Standing and clapping during the gospel might have made Ron Anderson a little less conspicuous two years ago when he first brought his congregation to the basement of one of Harlem’s most famous restaurants. Anderson, 35, is white and blond and an accountant from Ogden, Utah, who would look out of place even as a tourist at Sylvia’s Restaurant. But every Sunday for almost a year beginning in 1997, Anderson, 35, led a group of Mormons in prayer in the basement at Sylvia’s as the cooks in the kitchen upstairs prepared collard greens and fried chicken for the day’s gospel brunch. Sylvia’s president, Vann Woods, a fellow Mormon, offered the space to the branch when he heard Anderson was having a hard time trying to find another place to meet. Anderson said the community was accepting from the beginning, but added that Woods had one stipulation.

"We had to be out by 11 o’clock when they started the gospel brunch upstairs," Anderson said. By 1998, the church had found its current building, an inconspicuous one-room brick meeting hall vacated by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, at the corner of 129th Street and Malcolm X Boulevard. Since then, Anderson has been at home in Harlem even though he is one of the only white church leaders in the community. He said the economic issues facing his branch are far more immediate than the racial or religious questions, but his outlook on how to solve the problems comes from his firsthand experience with conspicuous racism. Anderson was 12 years old in 1978, the age all dutiful male members of the church are admitted to the priesthood and the year Kimball delivered his revelation. Anderson grew up in a small town outside Ogden, Utah, one that he called "frighteningly homogenous" and overwhelmingly Mormon. After graduating from high school in 1983, Anderson was sent to Johannesburg, South Africa, to

work as a missionary in the colored communities during the most virulent days of apartheid.

There he encountered what he called a more clearly defined form of racism. It also became a comparative study in America’s racial problems that he would put to use years later in Harlem. Anderson said that because in South Africa the problem was so stark and so obviously based on race, it was sometimes easier to deal with. The coloreds could focus on a singular solution, even if it did seem nearly insurmountable. In America, he said, the issues are not as clean and race

often becomes a catchall word for issues of class, skin color, empowerment and responsibility.

"In South Africa there was just more of a feeling that the coloreds controlled their own fate more," he said. "Here it is difficult. We don’t spend a lot of time, to be quite honest, talking about race." Instead, Anderson said his focus is more in keeping with the church’s central mission to help its members become more self-reliant. An issue he believes is especially relevant in the inner city and one he later saw come to fruition in South Africa. "I once had female member come to me who explained her hardships to me by saying, it is not my fault, it is not my fault," he said. "And it wasn’t her fault, but eventually I told her, ‘It may not be your fault, but it is still your problem’." The problems Anderson faces are the same ones most ministers in any church in his community face. They sometimes deal with issues of poverty and urban blight, unemployment, and drug and alcohol abuse, but, he pointed out, they also deal with having to address a branch that includes everything from the homeless to some of Harlem’s most successful businessmen. Anderson said the church is perfectly suited to handle many of the problems. The church runs its own welfare system, its own job resource program, and it offers short-term assistance to all members trying to find work. Family life and community involvement are essential to the church’s mission. But, he acknowledged, the issue of race never disappears. Anderson said that both inside the church and out there are some "obvious questions" that come up. The first is almost always the priesthood issue. "I give them the answer the prophet gave — because that is how the doctrine was interpreted by the leaders of the church at that time," Anderson said. "I don’t know if I have a better answer than that." Another common observation, most often made by children, is equally difficult for Anderson. It has do with the pictures that hang along the walls inside his congregation. Anderson said it is often noted that in other Harlem churches Jesus is depicted as a black man. In his church, all the pictures are of a white Jesus, which he says brings the inevitable question, "What color is the savior?" "The answer I give to that is that I have never seen the savior, personally," he said. "We only know that he was Jewish. When I was looking at the pictures of the Scandinavian savior, obviously the savior looked very Scandinavian and not at all Jewish. But if that helps you draw closer to the savior, so be it." Looking at pictures of the leaders of the church, the differences are also apparent. The church has had one black man in it General Authorities in history, the state of Utah is still only about 0.5 percent black and even at the local level, leaders like Anderson are most often white. Anderson said one of his most memorable conversations about race and the church was with a friend named Clifford Munnings, whom he met shortly after arriving in New York. "Well, Harlem was founded by people who were white," Munnings said. "But it is ours now." Still, there are critics of the church, several of whom are former Mormons, who say attitudes that existed in 1978 are still very much alive today. Bobby Axelson, 52, who runs the Freedom from Mormonism foundation in Las Vegas, left the church in 1978 and shares the feelings of many. "The inconsistencies are stunning," he said. "They have gone back and sanitized their own cannon and their prophets." It is an accusation Darius Gray does not deny, but he said that the changes the nation has seen are reflected in the church’s struggle too. "We are learning," Gray said. "In this country and in this church."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------